6.6 Basic Waveform Interpretation

Interpretation of ultrasonic waveforms always requires proper training and experience. A trained operator can use echo characteristics to determine the geometry of a flaw as well as its location. This section provides a simplified overview of some commonly encountered indications. Note that these examples are intended for concept demonstration only, and are not intended as a substitute for interpretation by a trained operator who is aware of the requirements of the specific test at hand.

In all cases, initial angle beam calibration should first be performed as discussed in section 4.3. Most test procedures will also specify how to set a reference gain level, using the side drilled hole in an IIW block or a similar reference reflector to normalize the starting gain level for an inspection. Once this has been done, testing can begin, commonly using the probe movement pattern described in section 6.4.

Peaking up

When an indication is observed during scanning, the next step is normally to identify the probe position that produces the maximum reflected amplitude. This procedure is known as “peaking up”, and it is performed in two directions, first along the length of the weld (transverse direction) and then with respect to distance from the weld (axial direction). Peak memory software that draws an echo envelope is very helpful here for documenting the probe location that produces the largest signal.

| Transverse peak-up | Axial peak up |

The transverse peak-up procedure can also be used to determine the transverse width of the flaw. A common procedure is the “6 dB drop technique”, demonstrated in the graphic below, in which the probe is moved from left to right while noting the two points where the maximum reflection that is seen at the middle of the flaw drops to 50% at the edges. The distance between the probe center at each of those two points represents the width of the flaw. Other procedures may use a different amplitude point as the reference.

Examples of flaw indications

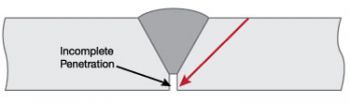

(a) Incomplete penetration – This typically generates a very strong reflection from the base of the weld at the first leg /second leg boundary. The same indication is observed if the weld is scanned from the other side.

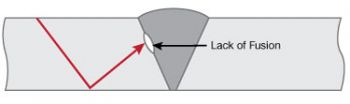

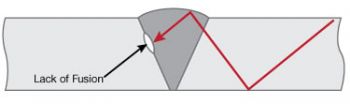

(b) Lack of fusion – This typically generates a strong reflection with fast rise and fall time in the second leg from one side of the weld, and a weaker third leg indication or nothing from the other side. Prolonged response with axial scanning indicates cross sectional length. The first video below shows the signal when the weld is scanned from the side with the fusion gap, and the second video shows the same reflector as seen from the other side.

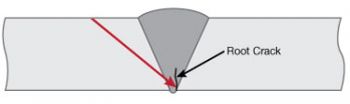

(c) Root crack – This typically generates a first leg signal from bottom of weld, with the crack indication appearing close to a reflection from the bottom weld bead. The first video below shows the signal when the weld is scanned from the side with the root crack, with the crack indication in the gate and the weld bead echo following it the L1 graticule. The second video shows the same reflector as seen from the other side, with a strong bead echo preceding the crack indication.

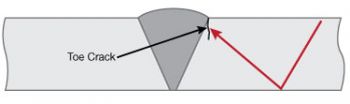

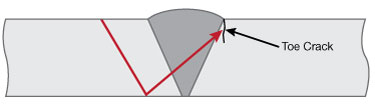

(d) Toe crack – This typically produces a second leg signal from top of weld, ahead of crown echo when tested from one side and following crown echo when tested from the other. In the videos below the crown echo is located at the L2 graticule. The first video below shows the signal when the weld is scanned from the side with the toe crack, and the second video shows the same reflector as seen from the other side. As non-planar defects, cracks can often produce multifaceted reflections.

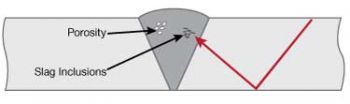

(e) Porosity and slag inclusions – These typically produces a cluster of echoes that exhibit multiple facets as probe is rotated. Indications will often be not as strong as those seen from planar defects and large cracks. Slag can look very similar to porosity. The multi-faceted echo may not be as strong as from porosity, and peak shapes and amplitudes will change rapidly with probe rotation.